The Science of Being Clutch

By Mike Silva

I'm going to describe to you two different, fictitious people in the same fictitious scenario with differing fictitious outcomes.

The purpose of this is to see how you would describe their reactions to their set of circumstances and what characteristics or traits you'd assign to each one.

Scenario: Two people are taking a timed test. There's a 60-minute allotment to answer 50 questions. Four minutes remain and each person has six questions left to answer.

Person A: To this point, Person A is confident about his performance. He knows the source material, he's sure of himself, and he hasn't let the clock impact his process of deducing his answers. This doesn't feel any different than homework from last week. He studied and practiced and actually comprehended the material ad nauseam. There's plenty of time to turn in a strong set of responses to the final six queries.

Person B: Person B is on a roller coaster. Each question welcomes either extreme confidence bordering on cockiness or it comes with a blank stare. The tougher questions make him second guess himself on how he responded to the easier questions. He's sweating, his heart rate is accelerated, and he's done the math: 50 questions in 60 minutes is about 1:12 per question. At this pace, he's got time to answer just three questions. What if I fail? he wonders. What if the ones I thought were right aren't right at all? Why did I mark "c" in four straight questions? That can't be right, can it? Dammit, now just three minutes remain!

This is a very relatable scenario. How often have we been in either shoes? Most likely we've experienced both sides of the spectrum. But how would you describe each person?

Person A is prepared. He's confident. He's unshaken. Simply put, he performs well under pressure.

Does that mean Person B is the opposite? Is he unprepared or does he lack confidence? Not necessarily. But you could say he doesn't perform very well under pressure.

Where it gets even trickier is if we try to label each one. We truly don't have any other information to jump to such a finite conclusion of assigning a label.

Consider the following possibilities:

Maybe Person A's best friend took the test earlier and gave him several answers. Is Person A then a cheater?

Maybe Person B and his girlfriend are in a fight. Maybe Person B has a close relative that's in poor health it's distracting him at the moment.

Again, we don't have enough information to make a final assessment. There are too many external factors to consider to which we aren't privy at the moment.

Let's make this even more complicated. Let's say the tables are turned. Person A is the one with the ailing relative and he's in a fight with his significant other. Person B has several answers ahead of time and is still struggling to ace this test. How do you explain this?

Long story short, this comes back to one way we originally described Person A: He performs well under pressure.

There absolutely is such a thing as being "clutch," when everything slows down and the pressure reaches a height that motivates rather than deters capability.

For years, people have been trying to figure out the science behind "the clutch gene." In sports, most prevalently, we have this conversation all the time. For every clutch player there's the counterpart: The choke.

But what predicates which side of the spectrum one falls into? Are you automatically clutch in nature or choke in nature, or is it a mix that varies per scenario?

To understand this phenomenon, we have to observe the way the brain works. But first, let's look at the body.

Science has shown that gross motor skills (e.g. running, swimming, punching) improve when pressure amplifies. Think about life or death situations, where a grandmother is able to lift a car off the ground.

Fine motor skills (e.g. typing or writing, picking some up with your fingers, throwing a ball), on the other hand, see a more complex correlation.

Performance of complex skills follows an "Inverse U" pattern: Skills improve until they reach a height, a breaking point or threshold, where they then begin to dramatically decline. Think about a pitcher, worried about runners on base instead of the batter at the plate, that locks up and throws a wild pitch.

Physiologically, when we're under an intense amount of stress, several things happen. We sweat, our heart rate increases, we may get that sudden rush of butterflies, our joints become stiff, our muscles contract, our words come out a little choppier than usual.

Think about that feeling you get when a cop pulls you over, or when you were younger and you approached a girl to ask her on a date, or your first job interview.

Now, you may not have exhibited all of the stress indicators listed out above, but to a varying degree, some of those things indeed happened. Your nerves were up. This is uncharted territory. You don't have the experience. You don't know what the outcome will be.

But fast forward just a bit. Guys, isn't it a lot easier to approach a girl now than it was when you were 12? Isn't a job interview a lot less stressful than the first one you've ever encountered? Unfortunately, seeing flashing red and blue lights is still a bit unnerving.

The point here is that of conditioning. This is where the brain comes in. Sure, approaching an attractive member of the opposite sex can still feel challenging, just like a job interview hasn't become comparable to ordering a cup of coffee, but our experiences have conditioned us to not expect the worst.

When we become more focused on the task rather than the outcome, we're able to maintain a proper focus. We're no longer worried about what could go wrong. Hell, even getting overly excited about what could go right can be enough to get your nerves to an unmanageable level.

You would think intense pressure means you'll be stronger and faster, but with less control. At most times, that seems to be true. But with top performers, the truly focused, we know that isn't the case.

Have you ever heard someone describe a great quarterback as having amnesia? What this means is great players have the ability to make a mistake and immediately forget about it.

While they definitely should learn from theirmistakes (don't force a pass into double coverage, dummy!), they're wise in moving on and not dwelling on them.

Overthinking what went wrong makes you consider what else could go wrong. Instead of focusing on the cliche "one play at a time" and being task-oriented, they think of the outcome. I hope I didn't lose us the game.

So is "clutch" something innate or can it be learned? The good old nature vs. nurture debate rears its head again.

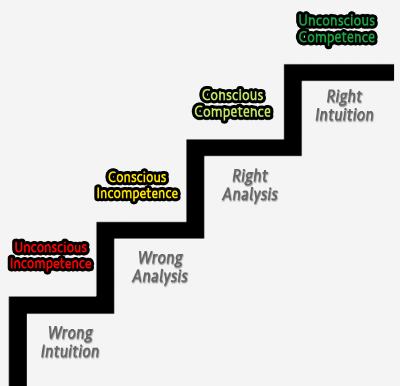

In short, you can definitely condition yourself to become clutch. To visualize this, let's take a loot at this figure:

Competence Chart

There are four levels of competence:

Unconscious incompetence - You don't know what you don't know.

Conscious incompetence - You know you don't know it.

Conscious competence - You know you know it.

Unconscious competence - You don't know you know it.

The goal is getting to unconscious competence. This is when an ability becomes second-nature. Your level of mastery has reached such a height that you're not consciously thinking about the action, you're just doing it.

Think about mastering a recipe. The first couple of times you cook this dish, you're measuring everything out, timing out each step, checking constantly to see if your food is done.

The more you cook this meal, the easier it gets. It becomes an eyeball test. You can look at that steak and know when it's time to take it off the grill.

The levels of competence are quite visible in sports. A young rookie QB gets his first action under center.

He's wide-eyed and doesn't know what to expect (unconscious incompetence). He comes to find out NFL defenses are way more athletic and skilled than college defenses and he struggles (conscious incompetence).

After a couple of games, he starts to get it and as he's completing passes and winning games, he's feeling good about himself (conscious competence). Then he gets to a tough, 2-minute drill to lead his team to victory. He's calling audibles at the line because at a glimpse he's diagnosing what defense he'll see each play. He's executing each play, running back to the line of scrimmage, and driving his team down the field (unconscious competence).

Now, we can't accurately simulate every high-pressure moment and we certainly can't anticipate how we'll respond without proper experience. It's also probably not wise to seek out high-pressure situations just for the sake of practice.

That said, there are some things we can control:

Keep our eyes on each underlying task instead of looking ahead to the outcome.

If you make a mistake, learn from it and move on. One neat trick to get used to overcoming mistakes: Try doing menial tasks (brushing your teeth, opening doors, pouring water) with your non-dominant hand. You're going to be clumsy and make some messes doing so, but as a result, your psychological response to making mistakes strengthens. It also forces you to focus on tasks while making failures feel less important.

Always be prepared. You can never be too prepared.

Practice your craft until you reach a level of unconscious competence. Make it second nature.